Cyclin-dependent kinases

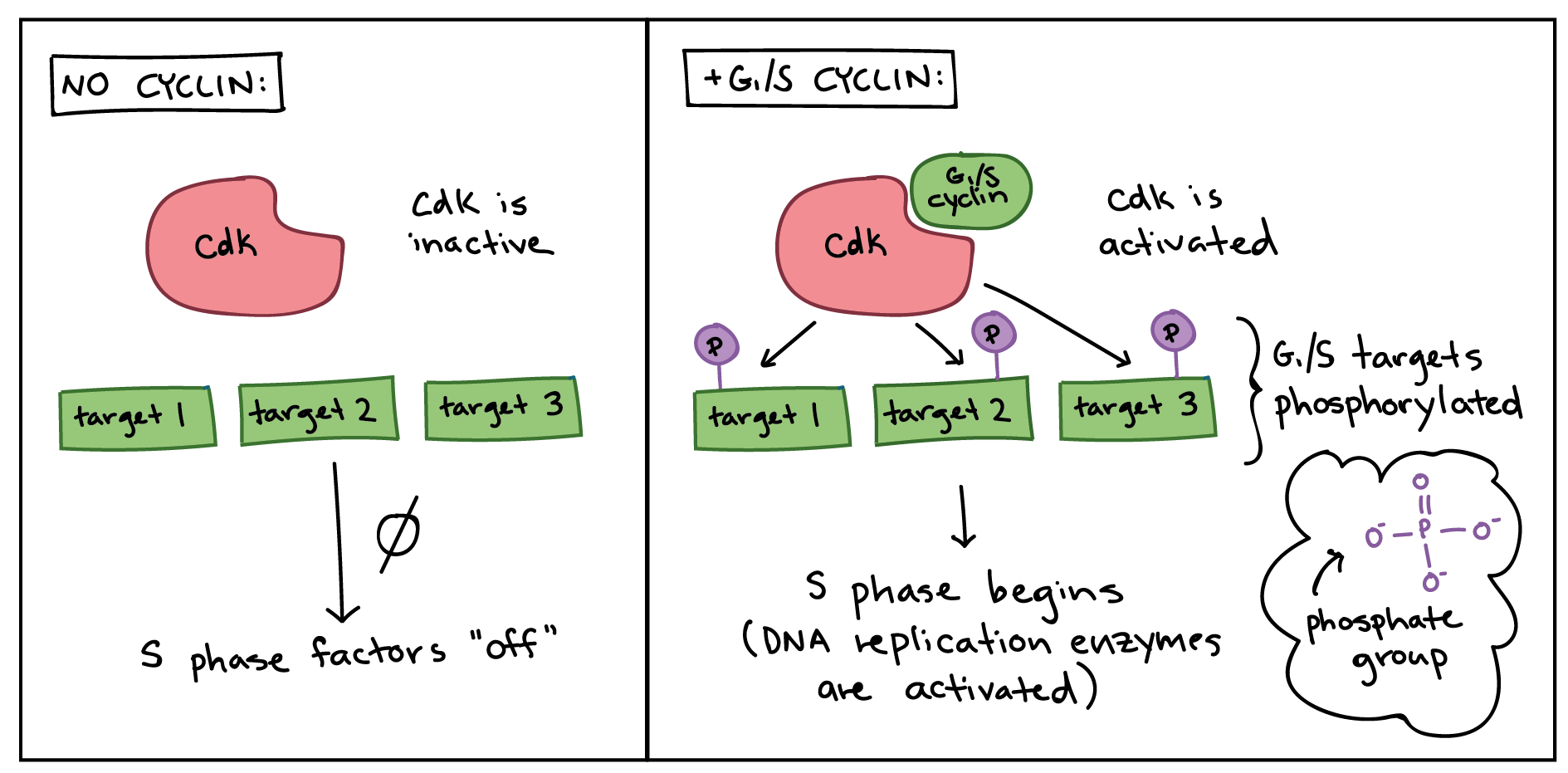

In order to drive the cell cycle forward, a cyclin must activate or inactivate many target proteins inside of the cell. Cyclins drive the events of the cell cycle by partnering with a family of enzymes called the cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks). A lone Cdk is inactive, but the binding of a cyclin activates it, making it a functional enzyme and allowing it to modify target proteins.

How does this work? Cdks are kinases, enzymes that phosphorylate (attach phosphate groups to) specific target proteins. The attached phosphate group acts like a switch, making the target protein more or less active. When a cyclin attaches to a Cdk, it has two important effects: it activates the Cdk as a kinase, but it also directs the Cdk to a specific set of target proteins, ones appropriate to the cell cycle period controlled by the cyclin. For instance, G/S cyclins send Cdks to S phase targets (e.g., promoting DNA replication), while M cyclins send Cdks to M phase targets (e.g., making the nuclear membrane break down).

In general, Cdk levels remain relatively constant across the cell cycle, but Cdk activity and target proteins change as levels of the various cyclins rise and fall. In addition to needing a cyclin partner, Cdks must also be phosphorylated on a particular site in order to be active (not shown in the diagrams in this article), and may also be negatively regulated by phosphorylation of other sites.

Cyclins and Cdks are very evolutionarily conserved, meaning that they are found in many different types of species, from yeast to frogs to humans. The details of the system vary a little: for instance, yeast has just one Cdk, while humans and other mammals have multiple Cdks that are used at different stages of the cell cycle. (Yes, this kind of an exception to the "Cdks don't change in levels" rule!) But the basic principles are quite similar, so that Cdks and the different types of cyclins can be found in each species.

Comments

Post a Comment